Anterior segments

Olivier Scatton

According to the Couinaud classification, the anterior sector is a three-segment region, including the segments IV, V and VIII. The common point of all these segments is the outflow, provided by the middle hepatic vein (MHV): its position is 1cm above the gallbladder bed, and goes along the « Cantlie’s line», separating the segment IV and V-VIII, through the vena cava.

The laparoscopic exposition of this era remains difficult, especially the right part of segment VIII and IV. The approach of segment IVa or VIII is totally different and more difficult than segment IVb, which is considered as a peripherical segment, far from the caval confluence. This latter will not be addressed in this chapter and belongs to an easy anatomical area.

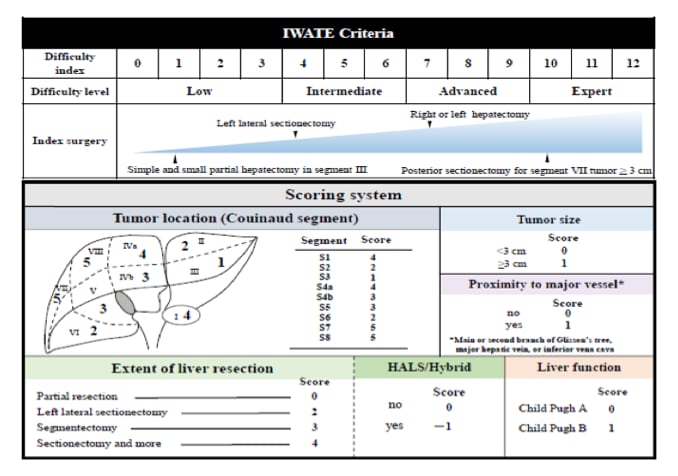

According to the IWATE classification (1), hepatectomies in segments IVa, V and VIII are considered as difficult resections that required advanced skills.

However, tumorectomies of lesions smaller than 3 cm should be distinguished to anatomical hepatectomies. When considering anatomical resection in segment VIII, surgeons should be aware of the highest level of complexity of this resection, which requires an advanced or expert level to be safely performed (1).

The safety and feasibility of central hepatectomy or right anterior sectionectomy has not been fully documented yet.

The first International position on laparoscopic liver surgery in 2008 in Louisville (2) and the second consensus conference of Morioka in 2014 (1) have stated that resections in the left anterior segments have become a standard of practice.

However, resection in right anterior and especially superior segments remain challenging procedures that cannot be adopted worldwide without more extensive evaluation.

During the Southampton Guidelines conference (3), the panel expert agreed and confirmed that resections, especially anatomical ones, are highly complex and require advanced expertise. As compared to minors resections performed in the anterolateral sector, segments IVa-V and VIII minors resections are associated with more bleeding and greater operative time.

In the Institut Mutualiste Montsouris (IMM) experience reported in 2102 (oral communication), the operation was 90 minutes longer in average, and blood loss was increased by 2 fold in case of segment IVa-V or VIII resection, when compared to the anterolateral sector. Although more complex, the mortality and morbidity rates remain equivalent to other types of minor resections probably because these resections are performed in expert team. The IMM team recently proposed a new scale of difficulty based on the need of anatomical resection and tumor location. As an example, anatomical resection in the supero-anterior segments is quoted 2 on a scale of 3 (maximum difficulty).

Central hepatectomy removing segment IV-V and VIII and right anterior sectionectomy are probably the most difficult operations to perform by laparoscopy. Very few teams reported their experience. Recently, the Samsung team from Korea (4) reported a case-Matched study with propensity score matching comparing open to laparoscopic anatomical resections of centrally located tumors. Among 20 laparoscopic resections, two required conversion due to bile duct injury and anatomical distortion, respectively. The duration of surgery was significantly longer in the laparoscopic cohort but there was no difference in terms of morbidity. The hospital stay and blood loss were interestingly equivalent. A Glissonian approach was widely used in this team. Deep location of the tumor significantly affected the operating time as compared to superficial lesions. The same team stressed on the need of previous extensive experience before starting such central hepatectomy by lap.

Overall, the conversion rate ranges between 7 to 17% irrespective of the type of resection (from minor to major). Although the conversion rate is lower in case of minor resections, the superior location of the tumor is significantly identified as a risk factor of conversion among five studies that focused on the conversion causes (5-9).

On a technical point of view, Segment IVa, V and VIII do not need transthoracic approach as described for posterior segments. However, a full mobilization of the right liver can be useful in order to nicely expose segment VIII and V, and only rarely, the right approach of segment VIII can be done with a transthoracic approach (10).

The patient can be put in a supine position with (so-called French position) or without the legs apart. Five trocars are often used, with their position depending on the localization of the tumor: if anterior, the trocarts are put along an inverted T-shaped line, as for a left hepatectomy (11). For more posterior or right-sided tumors, trocarts are disposed on an J-shaped line, as for a right hepatectomy, with a thick pillow or gelatine leaf behind the patient to offer a slight pivot.

Anyway, in the largest series of central resections, the transthoracic approach was never required. Intraoperative ultrasound examination is mandatory, in particular to follow the transection plane along the right and middle hepatic veins. Moreover, an echo-guided needle punction of segments VIII or V with injection of vital blue dye can be realized, to help the performance of an anatomical resection.

Before any parenchymal transection, the hepatic pedicle should be controlled to allow a pringle manoeuvre, if required. Korean teams basically quickly approach the glissonian segmental pedicle in order to temporary clamp the inflow (4). This can help to reduce bleeding and achieve an anatomical resection based on ischemic zone.

Given the proximity of the middle hepatic vein in the anterior and superior segments, large lesions or lesions close to the vessels can required a previous control of the common trunk of Middle hepatic vein. For that purpose, learn to control the common trunk is very helpful. After lifting the left lobe on the right, the vascular control begins by lowering the segment 1 and to dissect free the Arantius ligament. The space between the vena cava and the MHV should be exposed and dissected in order to safely control the trunk. When the posterior aspect of the MHV is seen, a dissector is passed under the MHV and the dissection continues horizontally blindly along the vena cava in order to reach the vena cava confluence of the veins. The left lobe is then put in its anatomical position in order to see the tip of the dissector and encircle the trunk. Controlling the venous outflow is a special maneuver that can dramatically decrease the blood loss and conversion rate as well. This venous control requires previous experience that can be achieved after the learning curve of left resection (11).

Conclusion

The laparoscopic anatomical resection of lesion within the anterior segments can be safely realized, by pure abdominal approach, with precautious hepatic inflow and outflow control and echo-guided parenchymal transection. These resections are technically challenging, and require previous experience in easy and intermediate laparoscopic liver resection.

Small and superficial lesions located in the right anterior sector are easily resectable while deep and /or large lesions are probably much more difficult to remove according to the widely recognized difficulty scales. In this latter situation and especially when an anatomical resection (including central hepatectomy) is envisioned, the risk of conversion, the blood loss as well as the operating time are increased. Given the risk of bleeding related to the proximity of the middle hepatic vein, it is strongly recommended to learn how to control the outflow, i.e. the common trunk.